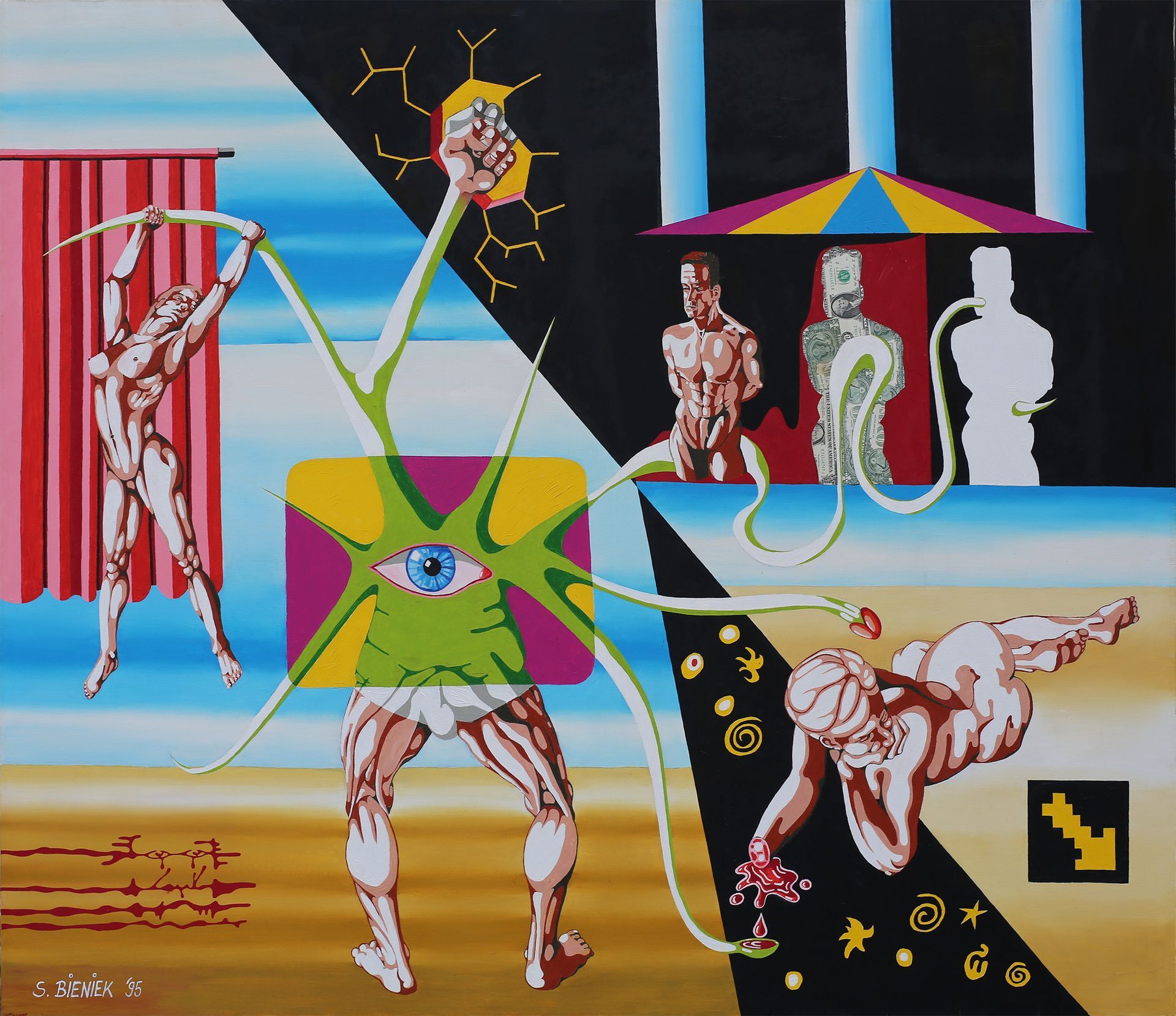

“Media Democracy - Rendezvous of Truth” is a media-critical painting by the Berlin artist Sebastian Bieniek, created in 1995 (before his studies and at the age of 20).

Sebastian Bieniek about his own artwork:

The work explores in particular the filters and narratives that the media install between voters and those in power, such that practically no real connection exists between them anymore, and everything takes place only on the level of media projection,

which is constantly increased to the advantage of the media and those in power and to the disadvantage of the voter due to the resulting dissonance (which can supposedly only be resolved by even more media or media activity).

The voter is trapped and lost in a labyrinth of media narratives created by the media, so that virtually everything (every story) the voter could oppose to those in power is transformed into its opposite and thus never fulfills its function as criticism. It remains trapped by the media filter that acts like a shield around those in power.

Sebastian Bieniek, 3rd of august 2009

The work is painted in oil on canvas and measures 120 x 150 cm. It is signed in the lower left corner on the front and signed and titled a second time on the back.

"Media Democracy - Rendezvous of Truth", painting by Sebastian Bieniek

With his work “Media Democracy – Rendezvous of Truth”, Sebastian Bieniek creates a complex and provocative panorama that inevitably draws the viewer into the maelstrom of our contemporary media landscape.

The painting, which in its conceptual density is reminiscent of a kaleidoscopic collage, calls for a renewed reflection on how truth and power merge in the digital age, influencing, supporting, and nourishing each other.

In typical Bieniek fashion, the image is not a static representation, but a multifaceted exploration of the mechanisms of information dissemination. The central composition depicts a kind of rendezvous—a meeting—between different media forms and actors: social networks, news agencies, political icons, and faceless avatars. These figures appear to exist in a symbiotic, yet also parasitic, relationship to one another, and above all, in an inseparable dependency, like a body to its organs.

At the center of the painting is an oversized and dominant eye, reminiscent in its pictorial use of the Eye of Horus. This is embedded in a kind of screen supported by the lower body of an old man.

Branches sprout from this screen, and twigs grow from the branches, as if it were a tree. The unnaturally rounded shape of the branches makes them resemble a snake, around which people are depicted. People who look away, people who disappear, are distracted, or who are merely placeholders in a frame. The scene evokes the story of Paradise, the "Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil," and the serpent winding its branches. A naked woman lying on the ground bleeds, her blood nourishing a branch of the tree, while another takes the form of a phallus and approaches her from behind. Here, too, one might recognize motifs from one of the countless stories in which Jupiter, sometimes as a snake, sometimes as a bull (of Europa), approaches and impregnates her. In this painting, however, the impregnator is not a god, but the media machine, which spins on and on, always only around itself.

The color palette is deliberately reduced to strong and vibrant primary colors such as red, blue, yellow, green, and magenta, reflecting the exaggerated nature of the medium but also creating a certain artificiality and thus distance from the depicted figures. They are not people. They are puppets.

The use of separate colors in 20th-century printing techniques reinforces the impression of a filter that lies on the actual level of reality, thus preventing a view of it.

What makes this work particularly distinctive is the subtle irony with which Bieniek questions the illusion of transparency and authenticity in media-driven democracy. The "Rendezvous" appears as a meeting of masks—an allusion to the facade often maintained in the digital world. The painting invites the viewer to penetrate the surface and question the mechanisms that shape our perception.

Sebastian Bieniek succeeds here in a frightening way in bringing together the complexity of our information society in a single, powerful composition. “Media Democracy – Rendezvous of Truth” is not only an artistic call to vigilance, but also a mirror of our times, which, in its visual density, reveals an almost frightening truth: In media democracy, truth is no longer solid ground, but a fleeting place to be explored, and one that presupposes the explorer's own responsibility.

Text by Eugeniusz Stankiewicz, 2016

1. In the beginning was control, or at the center is an oversized eye

Detail (the tree growing from a monitor) with a Eye of Horus in it)

"Media Democracy - Rendezvous of Truth", painting by Sebastian Bieniek

The all-seeing eye is at the center of the painting.

The Eye of Horus (Udjat Eye), which stands at the center of the painting "Media Democracy - Rendezvous of Truth," holds a special, sometimes archaic and even prehistoric, significance in many cultures. Overall, it can be said to represent "omniscient knowledge," which can, of course, also be interpreted as a form of surveillance. Indeed, the depiction of the "all-seeing eye" in many cultures, just as in J.R.R. Tolkien's "The Lord of the Rings" (where it is portrayed as Sauron's Eye), represents a power-hungry (in the form of the Ring), not to say power-addicted, machine.

The function of the eye, namely seeing and monitoring through seeing, is explored philosophically and sociologically in Michel Foucault's book "Discipline and Punish," which the artist Sebastian Bieniek, incidentally, thoroughly examined in 2000 when he collaborated with the prisons in Rennes, France, and Celle, Germany, on the installation"Life is Bad" ("Die Welt ist schlecht" & "Le Monde est cruel"). Therefore, one can say that "critique of state surveillance" is indeed a common thread in Bieniek's work.

The essentially immanent and ubiquitous forms of surveillance of everything that have arisen through the Internet and a (one has to say it) enforced “online life” have given the eye in Bieniek’s painting a new, not to say prophetic, relevance, meaning and importance.

Never before in the entire history of mankind has so much been seen, recorded on data carriers, noted, repeatedly evaluated and monitored as today.

From the perspective, or according to the narrative, of today's tech giants, who have made the analysis of recorded data their business model, the surveillance of everything is supposed to be good and lead to a kind of surveillance paradise. This is a paradox when one considers Foucault's book, which sees and describes surveillance not as part of a paradise but as a prison practice. But it is precisely this paradox that propels us forward in the painting and its narrative.

We see an eye, the size of a head in relation to the body that bears it, perched atop the lower body of an old man clad only in briefs. It is framed within a screen the size of a television. From this screen extend branches and twigs, transforming the lower body into a trunk. Their round, elastic appearance is reminiscent of a snake's body, thus bringing us to the image of a snake and a tree, and consequently to the biblical story of Paradise.

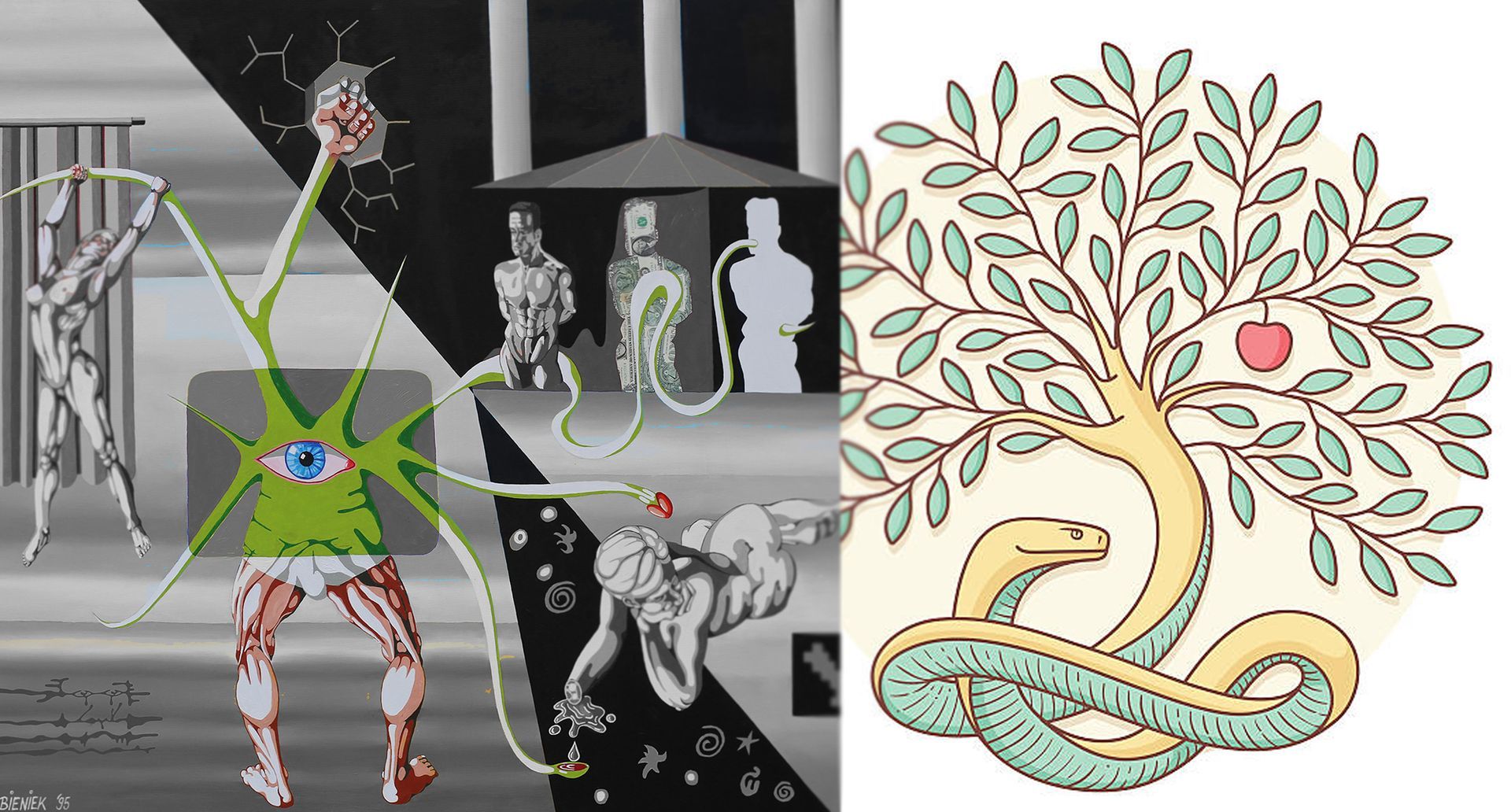

2. The "all-seeing eye" becomes the "tree of knowledge"

In Sebastian Bieniek's painting "Media Democracy - Rendezvous of Truth", the "all-seeing eye" becomes the

biblical tree of knowledge.

As can be seen in this image, a tree emerges from the eye, which rests on the legs of an old man and is located within a screen (television or computer monitor). A tree whose branches wind like the body of a snake. A tree, therefore, that becomes a snake, which brings us to the iconography from the biblical story of the Garden of Eden. The Tree of Knowledge.

The red apple appears to be the acorn of a phallus. Is the Tree of Knowledge, then, being portrayed here as a media-dominated instrument of manipulation and control? That, at least, seems to be the artist's message.

For Bieniek, therefore, cognition is merely a kind of program and a sequence of commands, not the knowledge stylized in the Western tradition that allows the knower to see more than others. Quite the contrary. Bieniek denies the measurability of knowledge in the sense of measuring depth or breadth. For the artist, more knowledge and more cognition simply mean that more control is available, and this increased control enables the execution of more commands.

The knowledge presented here as control over a continuum of authority may at first glance appear to be a pessimistic view of the world, but only at first glance. If one considers this metaphor further, it also opens up an opportunity and the possibility, conversely, in a hermetic sense, of gaining knowledge, understanding, and everything connected with it by regaining control over oneself.

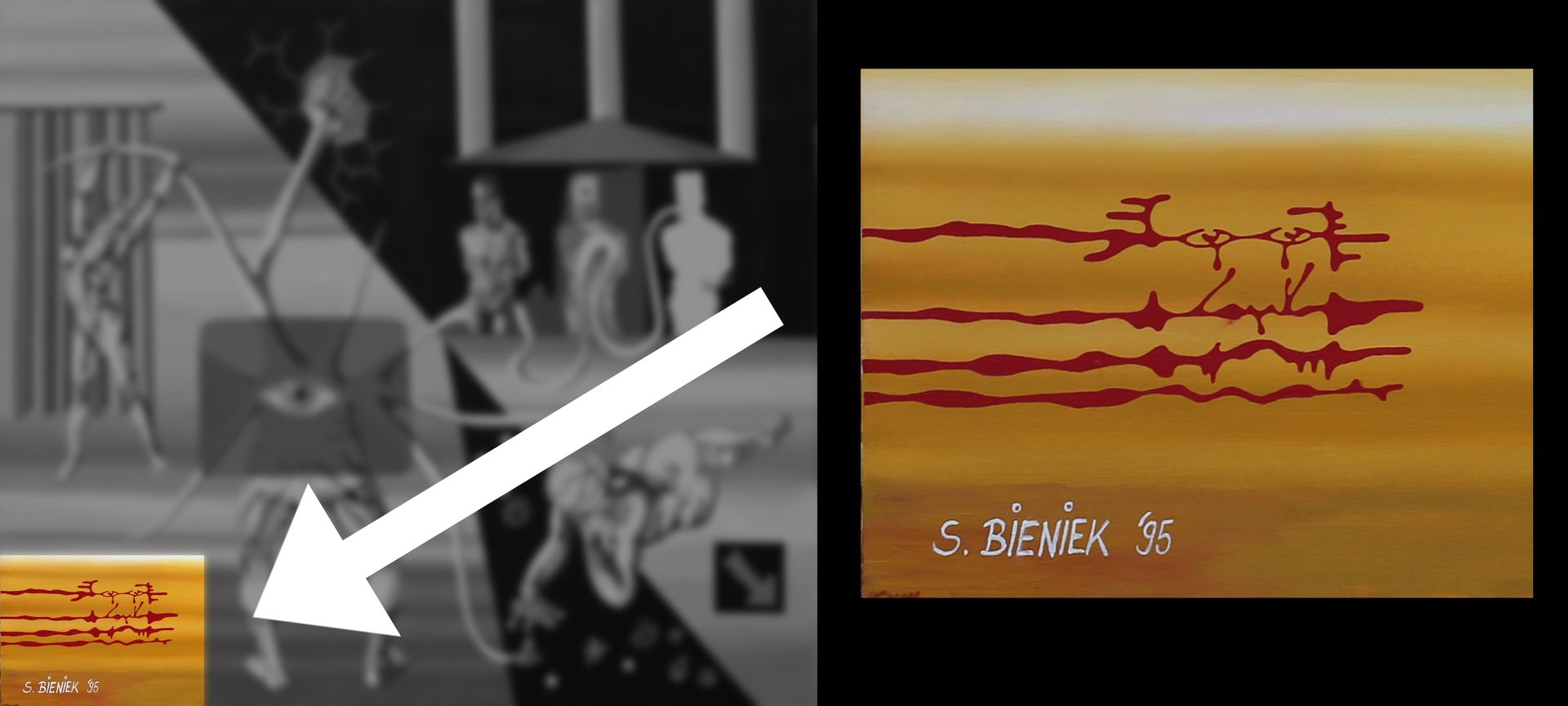

3. Pareidolia and the threshold to loss of identity

Pareidolia and the threshold to loss of identity, detail from the painting

"Media Democracy - Rendezvous of Truth" by Sebastian Bieniek.

A weeping face dissolving into the dry sand of the desert, or just pareidolia, a face that has been misinterpreted?

The context may answer the question. The detail of the face, composed of lines and dissolving like branches or liquid, is located in the lower left corner, right next to the signature, of Sebastian Bieniek's painting "Media Democracy - Rendezvous of Truth." Does media-induced manipulation dissolve our self-image, or does it even determine it?

If one were to believe the artist: yes. The individual, therefore, exists only nominally and merely as a label, as something unique, and reality is a deliberate standard created by the media and other sets of rules. Thus, the artist's view of human individuality coincides with his view of democracy. The artist sees both only as labels and not as reality.

4. Anti-capitalism and Rambo in the temple of money

Anti-capitalism and Rambo in the temple of money, detail from the painting

"Media Democracy - Rendezvous of Truth" by Sebastian Bieniek.

The “tree of knowledge” sprouting from the media seems to wind itself around people like a snake and capture them.

The three figures he began undergo a metamorphosis in three stages. In the first stage, the man is naked, idealized, but still as "God created" him. In the second stage, he is covered with dollar bills (money) that lie on him like a mask, overgrowing everything that once represented him. His face and his appearance are now only a representation of money. A red area rises around him, resembling a graphical representation of a stock market price chart. At first, the price rises, then it rises even more, and then, quite suddenly, it falls to zero, and there is nothing left—almost like in so many fairy tales where money suddenly transforms into stone or even excrement.

Behind him, further to the right, stands the third and final figure. The serpentine branch no longer winds around the person but, like the tip of a lance, has pierced their mouth, and appears to have passed through their throat, lungs, and entrails, exiting the body again at the lower end of their intestines. We see the sharp, fang-like end of the branch emerging from the abdomen of the last figure.

In the third and final stage, the human being is nothing more than an empty shell—perhaps drained of life. These three stages can be read chronologically like the stages of a fatal illness.

The three figures stand like the columns of an ancient temple whose roof, in a rainbow-like pattern, consists of three colors: magenta, cyan, and yellow. These are the colors found in every inkjet printer and thus represent the color spectrum of both printed media and everything else that can be printed, from documents to banknotes.

The artist used a photograph of Sylvester Stallone as a template for the first figure and the outlines of the following ones. In the 1970s and 80s, Stallone, like no other, shaped and glorified US capitalism and imperialism in his films like Rambo as the "way of a winner who wins alone against all the world's armies" (as long as he holds up the US flag), thus allowing himself to be both used and richly rewarded by Cold War propaganda.

Incidentally, the Russian film director Nikita Sergeyevich Mikhalkov used the image of "Rambo" in a similar way in his award-winning 1991 film *Urga*, in the form of a poster at the end of the film. Rambo, as an ideological and propaganda icon (in the sense of "in the West you can do anything and in the East nothing" and "here everyone becomes a Hercules and with you a loser," i.e., "switch sides—come over to our side, then and only then will you also be a winner"), and the introduction of video technology as a distribution medium on the one hand, and a new economic sector on the other, had contributed significantly to the collapse of the Eastern Bloc. Without video, the Eastern Bloc would very likely still exist today.

5. Media Libido and the Creation of Asexuality

(Media and Sexuality in a State of Defenselessness)

Media Libido and the Creation of Asexuality (Media and Sexuality in a State of Defenselessness),

detail from the painting "Media Democracy - Rendezvous of Truth" by Sebastian Bieniek.

Where in the classical depiction of the Tree of Knowledge a red apple stands out from the green of the tree and is the object of desire, in Sebastian Bieniek's painting "Media Democracy - Rendezvous of Truth" the red acorn of a phallus appears, from which a serpentine branch of the tree converges. In Bieniek's painting, then—and one might almost ask: what else?—sexuality is the driving force of desire, and not, as in the biblical story, wisdom (and one might also ask: "what good is wisdom, anyway?"). One is almost tempted to think that Bieniek is writing, or rather painting, the real story, and that the biblical depiction is merely Bieniek's allegory of the true story. A truly remarkable perspective and twist, since art is normally known for allegorical representation, and a reversal of this principle would be a novelty in every respect.

The glans in the lower third on the right side of the painting bends slightly downwards and towards the abdomen of a woman lying beneath it, who is turned away from it and is remarkable in many respects.

The woman is mutilated. Her right hand has just been cut off and is missing. The clean cut and the severed forearm bones are visible. The cut lies in a pool of fresh blood dripping into a spoon, which has become the end of another serpentine tree branch. She is therefore defenseless and in need of help, and in this state, she is being penetrated by the media who have become the tree, or at least this seems to be the next step and therefore the intention of the media tree.

6. Development aid, i.e., retro-racism, is the heroin of postcolonialism.

Development aid, i.e., retro-racism, is the heroin of postcolonialism, detail from the painting

"Media Democracy - Rendezvous of Truth" by Sebastian Bieniek.

In the detail from Sebastian Bieniek's painting "Media Democracy - Rendezvous of Truth," a woman with a severed hand is depicted. The woman is intentionally not portrayed with a specific skin color, as the artist wishes to avoid retroracism, namely the association of exploitation with a particular skin color. Exploitation knows no skin color, only social classes and castes. There are exploiters of every skin color, just as there are exploited of every skin color. Therefore, associating the class of the exploited with a specific skin color, just like any skin color quotas, is a form of tacit acceptance of racism, which Bieniek calls retroracism.

The principle of racism through reverse racism, in the form of forced liberation—that is, liberation through labels that is in reality subjugation—is also what the artist sees in development aid, for which he has found a metaphor in the image of a severed hand, its blood collected in a spoon and served to the person whose hand was cut off. Here, the person who cut off the hand is clearly portrayed as their savior, wanting to save them with their own shed blood.

This excerpt powerfully illustrates the hypocrisy and duplicity of postcolonial Western culture, which, just as it did 150 years ago, still exploits former colonies and treats their inhabitants like second-class citizens, the only difference being that today it calls it development aid instead of slavery. People on equal footing don't need anyone telling them how to develop, and those who see others as equals don't presume to tell them how to live. Imagine if someone from Africa came to the USA and told the Americans how to live, given that they have clearly contributed to more wars and suffering in recent history than the inhabitants of any other country on the planet.

7. Discourse or media cannibalism, due to in the beginning there was looking away.

Discourse or media cannibalism, due to in the beginning there was looking away, detail from the painting

"Media Democracy - Rendezvous of Truth" by Sebastian Bieniek.

While the Tree of Knowledge, which according to Bieniek essentially prevents all knowledge and which, for Bieniek, represents the media, is about to feed a woman with her own blood, she turns away and looks at a cursor (mouse pointer), the focus banner of digitalism. Whether it distracts her or whether she deliberately looks away (to avoid seeing) is hard to say; perhaps both, perhaps depending on whom you ask and whose perspective you adopt. Why do people look away, one would have to ask at this point. Which of the two came first is as easy or difficult to say as "whether the chicken or the egg came first." Whether looking away or distraction was the beginning is thus a question in itself. In any case, it seems as if both belong together like two sides of the same coin. Without the cursor, there is no distraction, and without the act of violence, there is no need for distraction and no demand for the progenitor of the digital, and thus for the digital itself. The desire to look away therefore creates the distraction, the welcome turning away, that is Hollywood, Disneyland, and the internet of this world.

The digital realm is thus merely a new layer of distraction, just as the tree itself and the media are merely distractions. These distractions were once new and suddenly became necessary because the previously known means of distraction were no longer sufficient. Something new, bigger, and more ubiquitous was needed, because distraction must always be omnipresent, and if it isn't, it will become so. It must creep ever deeper, into ever more holes and niches. It must dominate more and more - indeed, dominate everything. It must be so effective that the distracted person doesn't even see what their daily bread is, and if one were to believe the saying "you are what you eat," what they themselves are. They cannot and must not define it for themselves. They must ask what deprives them of knowledge - which is no knowledge at all.

But let's return to the feeding. Isn't the woman being served human blood on a spoon - even her own blood? Let's consider cannibalism now, both literally and metaphorically in this case, namely in its function as a closed system. One can see both self-sufficiency and brutality in it. Self-sufficiency, however, only if one disregards the severed hand, because devouring oneself is no longer self-sufficiency. One should almost say being devoured, because there is a second subject present who catches the blood and offers it to the woman on the green spoon from the Tree of Knowledge.

Ultimately, it is striking how this painting, regardless of the angle from which one approaches it, possesses a density of meaning that is incomparable to any other painting. It is no exaggeration to say that it is indeed a prophetic painting that - one might argue - says more about the world we live in than all the books and media in the world combined.